An Interview with Father Thomas P. Bonacci, C.P.

The Interfaith Peace Project Library

An Interview with Fr. Thomas P. Bonacci, CP

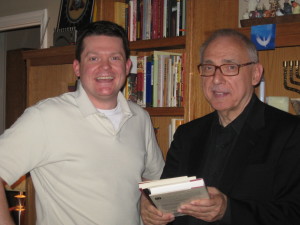

By Jeffrey Fleming

The Interfaith Peace Project Library was developed to provide a quiet, peaceful place where the soul can be inspired by the beauty, the poetry, the mysticism and the imagery of any and all faith traditions. It offers the seeker a place to study, to reflect, to pray and to meditate. A world opens to those who seek as their feet go 2 inches but their heart goes across the universe.

The library contains over 4000 books and numerous religious articles. Whether one is new to interfaith study or a seasoned veteran, the library offers a quiet environment for all.

The following is an interview by Jeffrey Fleming about the Interfaith Peace Project Library with Fr. Thomas P. Bonacci, C.P., executive director of the Interfaith Peace Project. Jeffrey Fleming, while working on his degree from Diablo Valley College, spent 4 months cataloging all of the books at the Interfaith Peace Project Library. The books were cataloged in order to have a record for insurance purposes, to have a listing of what is in the library for research purposes, to discover duplicates, rare books and documents, and to publish the list on this website for the general public so that people may come to the library and use the books.

This interview was edited by Susan Batterton, who regularly visits the Interfaith Peace Project library to find solace and discover the treasures of the faith traditions of human kind.

Jeff: How would you explain to a non-religious layman what the Interfaith Peace Project is all about and why it is important?

“Non-religious”, I don’t know what that means. One thing we intend to do is not to use those kinds of categories. The reference to a person as a “non” is not a sense of direction. The word religion is not universal to religious people. For example, in the Hindu system, there is no word for religion, yet no one would call them non-religious. They would use the word “devotee”: “I am devoted to the god or goddess.” The word religion implies a regulatory agency. A lot of people today make the distinction that “I am not religious, but spiritual.” I don’t believe the two are opposite one another, but they nuance something differently.

So the Interfaith Peace Project when it meets another person, before trying to explain anything about what we do, the explanation would come in the way we treat them. We would not treat them as not religious, as not Catholic, as not Christian, as not Buddhist, but would meet them precisely as the unique individual they are.

We would hope that the experience of the encounter with the Interfaith Peace Project would communicate more than the explanation. It would create a sense of hospitality, welcome and respect to the other person no matter what category other people put them in.

Some might refer to an atheist as not religious, which is not true. Atheism is a highly courageous spiritual activity. To believe that I should be a person of ultimate concern ethically, without any ultimate authority, is a very courageous stance to take. So we can very easily call that person not religious. But, I would find that person to be quite courageous.

The number one thing of the Interfaith Peace Project is not to meet other people as a “non”; not to meet them as a defect in judgment, but to meet them precisely in the uniqueness of who they are. Hopefully that experience will be the explanation of what the Interfaith Peace Project is.

We at the Interfaith Peace Project believe that there will be no world peace without religious peace and there will be no religious peace until people of faith meet each other, including atheists and agnostics and seekers and denominational, congregational believers.

Jeff: How did the idea of the Interfaith Peace Project come about? What inspired it?

I grew up in an interfaith neighborhood as a little boy and I didn’t know it at the time. I grew up in a blighted area of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, near these old mills where there was fire, graphite and coal dust. The sacred sounds around me were whistles and trains and tug boats There were four Synagogues in the neighborhood, an Episcopal church, a Polish Catholic Church, an Irish Catholic Church, and a Kingdom Hall, There were Eastern and Western Europeans, second generation immigrants. My family was a mixture of immigrants. People spoke Ukrainian, Russian, German Polish, English, Hebrew, and Yiddish; I thought that was what the world was like.

At 16 we moved from the inner city to the suburbs. I literally thought I died. My whole world was cut off. The American dream for some became my nightmare. I never quite figured out what had happened. What had happened was that I lost the interfaith world of multiple languages, multiple races.

I spent my entire college career and university career trying to recover that period of time. As I journeyed, I kept meeting people along the way, especially in New York City, who made me pay attention to my own experience.

For me, the Interfaith Peace Project wasn’t an idea that came along; it was an experience that was retrieved.

Jeff: In terms of the Interfaith Library, how did that come to fruition? We have the Interfaith Peace Project and we have the library which is an aspect of the Interfaith Peace Project. How did the library with 4000 plus books come to fruition?

There was a wonderful bookstore on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley called Cody’s. The second floor of that old bookstore was a wonderful place to go to see the books of the interfaith world. To me it was one of the best places in the United States to go to see the books. Many of the books I have were acquired from there.

When doing different dialogs, I hit upon the Christian Science Reading Rooms. Before I went to a Christian Science Reading Room, I thought Christian Science Reading Rooms had spiritual readings from the world. But they basically have Christian Scientist books and books that are compatible with Christian Science philosophy.

People would say, “I went to the mosque, I went to the temple, I went to the church, I went to the Cathedral” and I would have to say, “I went to the bookstore.” It sounded strange when they said, “Did you see that beautiful glass? Did you see the beautiful statuary? Did you see the beautiful architecture?” While I went to those places, my mind kept saying, “Have you seen the latest books that have come in?”

So Christian Science Reading Rooms and the discussion of others going to the different faith worship sites and Cody’s is all fused in my head. I said, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if we had Christian Scientist Reading rooms that were interfaith; where people could come in and lounge around and travel to the faith traditions of the world.” That is where the idea came from.

Jeff: How does the library assist with interfaith dialogue?

One has to be careful because interfaith dialogue suggests you should know something about the faith tradition of the person you are going to speak to. The temptation is to run to a book, find what Hindus believe, for example, and then when you meet with the devotee, you have something to speak to that person about.

Generally people do not believe what they believe nor have a devotion that they have because they read a book. Their devotion corresponds to their heart.

The purpose, to me, of the reading room or the library, is to have some information about the world faith traditions, but to be more inspired by the beauty, the poetry, the mysticism and the imagery of the other faith traditions. If anything, I think that sophisticated reading removes obstacles to the dialogue. But it is not let me get some knowledge of you I may get some knowledge of the tradition in which you practice, but I don’t have knowledge of you. So this is information toward what I can identify with; what opens my mind and heart, so I can come to you and speak with you. It is a dangerous kind of thing, because the knowledge I receive about your tradition can become the box I put you in or the stepping stones to meeting you.

The search for the books that you would put in this kind of a library is an ongoing thing. There are books to be removed and added as you go along with this dialogue.

Jeff: How do you determine the acquisition process and how do you weed them out of the collection? How do you determine which books need to be added to the collection?

We have a program called The Dialogue with Leaders. One of the questions we ask the leaders (not officials) is, “What books should be in the library?” We ask for their recommendations. What would be the devotional book, the scriptural book, the historical book, the inspirational book that would help people to appreciate the spiritual, faith and philosophical tradition from which they live?

Jeff: On the flip side of that, do you ever encounter a situation where you remove books for any sort of reason? Give me examples of when you would do that.

It is easy to stereotype another faith tradition, especially if you don’t know it. For example, voodoo is usually thought of as the way it is presented in a Hollywood movie, as someone having a doll and a needle and performing voodoo. In actual voodoo practice, it is not that way.

You can have books that look attractive, that read well, but are erroneous. Also you have books that are dated. They are not removed just because they are dated; some just need to be noted that it is dated and where the problems are in this particular book.

IPP is based on respect, love and kindness to another. Books that are ideologically driven, based on stereotypes or are attacks could be accidently purchased or purchased as a mistake and then on reading, we discover the book is inappropriate.

Jeff: I catalogued about 3500 books I believe there are 500 to 1000 more books that are in transition that I have not catalogued. Where did these 4000 plus books come from?

The Biblical book component has been in progress for 40 years. The core of some of the Biblical books and the theological books came from libraries that were being dismantled and the books discarded. These classic books are old and maybe some think it is time to get rid of them, but they are treasures.

There was a period of time where I started to get rid of books thinking that life should be simple. That’s why I don’t see the books as my personal possessions. They belong to the Interfaith Peace Project and the people that use them.

I search diligently and with other people for what would be appropriate. I find people are excited by the books. There is something about meandering through books and searching through books that invites people to contemplation, study and soul searching. It’s safe, secure, sacred, and intimate. A world opens to them. Their feet haven’t gone 2 inches but their heart has gone across the universe. In many ways these books are like keys to a thousand doors.

Jeff: The organizational method of the Interfaith Peace Project library does not use a formal classification system but there is a formula to it, especially with the sacred text section. What is the organizational method that you use for the sacred texts and why did you do it that way?

I wanted a classification system that makes it easy to find a book. Most libraries place all of the Jewish books in the Jewish section, all of the Buddhist books in the Buddhist section. To make it even easier they put them in alphabetical order by title or sub categories.

One of the key elements, we ask here at the Interfaith Peace Project is: “Is there such a thing as interfaith spirituality and if there is, how would you practice it?” It is one thing to access information about the individual’s religious tradition, but we are asking another question, “Is there such a thing as interfaith spirituality?” After these traditions have touched each other in a practitioner, a believer, a devotee or a seeker, what happens? What happens to that individual psychically, philosophically, spiritually, religiously, socially, ethically? What is their experience when insights are crossed over from various traditions after meeting people of the various traditions. That is intensely what we study. We examine that in other people through dialogue and through ourselves by soul searching. This invites us to discover that in many ways our own internal journey in the spiritual life is not neat and classified. We don’t have a Jewish section next to a Buddhist section, next to a soul section next to a body section, next to a nutritional section. We have a delightful mixture of all of those things. The sacred books are meant to reflect the interiority of this search.

The neighborhood I grew up in, while it could be predominately this or predominately that, the fact is when the kids played in the street they played together, mixed.

The books are deliberately mixed. I can go searching for the Torah and walk away with the Upanishads. The shelves, if you will, are practicing interfaith. They are out of classification much the way the world is out of classification. No one is where they used to be. The interfaith reading room is beginning to reflect that mixture.

Jeff: There are some very old, rare manuscripts in the collection. Can you tell me about a few of them?

There is a Buddhist prayer sheet from Cambodia, the content of which remains unknown. It may very well be known now because it has been researched at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. It is a gift of a person who had his own interfaith journey. He went from somewhat hostile to very, very open.

What is interesting about these older manuscripts is that they have real stories about real people and real families. The manuscript has a value in itself as an artifact but it is also a sign and symbol of real people’s journeys of faith.

Recently arrived is a complete set of Jewish Encyclopedias from 1903. The wonderful man who donated this in honor of his family tells wonderful stories of his growing up Jewish. The books he gave us from one hundred years ago are a window on a world now gone; a window on Judaism in Europe before the Holocaust. When you hold books like that and see the information within them, you become aware of what happens when religion is not associated with justice and peace, with respect and care. Faith can become a pathology. Pathology can become the instrument of murder.

The works of Josephus is a very ancient and very old classic manuscript. It is about the Jewish wars back in the New Testament period. It has wonderful insights into where much of the New Testament thought came from.

There is something very interesting about some of the manuscripts. Sometimes in the older books we get from second hand book stores or libraries that are being dismantled, there are letters and notes inside the books, if not inscriptions in the flaps. There are tremendous insights into people we have never met. Their writings, what they may have underlined, open up a whole new world for us.

I feel honored when people think they have a rare book and they think of this place as a home. One woman in particular in the Fremont area goes to second hand book stores looking for books she thinks would be appropriate for here, especially the older manuscripts.

One of newest additions to the collection that I was especially excited to see was the biggest book I have ever seen in my life, The Codex Sinaiticus. Tell me about that text and why is it such a beautiful and important addition to the collection?

The Codex is a facsimile of the oldest Bible we have intact, the Codex book from the 4th century. It gives us an insight into how the Bible as we understand in Christian terms has come together. There are books in the Codex that are not in the New Testament or in the Bible today.

These old manuscripts that we find open up not simply a book, but open up a world. These are a window on how language was used, how people understood the language, the cultures of people, the beliefs of people and even the beauty of their writings. To find these ancient manuscripts and to have copies of them such as the facsimile of the Codex Sinaiicus is like finding the penmanship of your ancestors; like finding a letter from your great-grandmother.

What we now call Scripture, at the time it was written may not have been called Scripture. Ancient people didn’t sit down and say let’s write Scripture. They wrote a letter to Barnabas and somehow that letter or portions of that letter became sacred to us. So to have these kinds of artifacts in the house opens us up to not only ancient texts but to contemporary texts. The letters, the reflections, the notes that people make on scratch pads, we need to keep them in a treasure box rather than in the recycle bin.

Jeff: There are a lot of categories or sections in the library. Some sections are much larger than others but all seem essential to the Interfaith Peace Project as a whole. I just want to talk about specific sections that sparked my interest. From your point of view, what is the importance of the Women’s Voice section?

The organization that is underneath the library is the first axial period. That is the period of time between 600 years before Christ and several hundred years on either side of Christ that religious traditions as we know them emerged. It was during that period of time the golden rule emerged. Karen Armstrong in her book “The Great Transformation” says that one of the defects of that period of time was the lack of women’s voice. So the great founders, if you will, the great sages seem to be one man after another.

I don’t easily accept that. When I hear that women in that period of time were not as appreciated, it causes me to ask the question, “Where were the women?” Because it is in that period of time and its aftermath that much of the feminine imagery emerged as we now understand it. The Gods and Goddesses of Hinduism were reformulated. The basis for the rise of Tara and Quan Yin are embedded. The story of Eve will be written in the form we now have it. There is the rise of Sophia in the wisdom literature of Israel. By the time we get to the New Testament period we see the spirituality about Mary, the Mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalene.

That led us to believe that the Interfaith Peace Project had to be concerned with retrieving women’s voice in ancient times and contemporary times.

The feminine voice does not rise in contradiction to the masculine voice. The feminine voice is necessary so that the masculine voice can be heard in its humaneness. The feminist, the women can no longer be ignored.

Look at the leadership of Interfaith Peace Project and the presence and leadership of women. It invites you immediately not to see women in terms of support systems, but to see women as co-equal seekers and searchers for women’s voice in ancient times. That’s a key to hearing women’s voice in contemporary times. All across the world right now, women’s voice is rising.

Jeff: The esoteric Liberation section. Tell me about that section and why you also think that section is important?

Liberation theology in the Catholic and Christian tradition was crushed in Latin and South American. But there is no doubt that its contribution is enormous. It was literally born out of the poor accessing the scripture in direct ways. Not to be antagonistic, but to be prophetic. That the Word of God was not so much a source of dogma, the Word of God was not a source of ethics in the theoretical sense of that term, but the Word of God is a source of a way of life, by which, to use the words of a woman, the lowly could be lifted up and the hungry well fed.

In every generation, it seems, we demonize certain groups of people. Sometimes the dominant religious group demonizes the minority religious group. Or the religious people demonize what they perceive to be non-believers. We, at the Interfaith Peace Project, are doing everything in our power to recognize the humanity of everybody.

So the esoteric section is not simply just esoteric with ideas, but behind every idea there is a real person having the idea. It’s people who have those ideas, which challenge conventional ways of thinking, who invite us not simply to change for the sake of change but to change for the sake of justice.

Jeff: Before I started this internship here, I had never heard of Thomas Merton. I bought my first book, “No Man is an Island” and have started to learn about his role in early interfaith work. How important is Merton as a pioneer in interfaith mission?

Merton is crucial for any number of reasons. First of all, he is crucial because of his human experience. He went from the coffee shops of San Francisco, to the hill country of Kentucky, to meeting the East. Merton was a contemplative monk and the stereotype is that a cloistered monk is cut off from the world and does not know what is happening across the street let alone what is going on across the world. But it is not true. Often times the people who practice the contemplative life are more in tune to what is going on in the street than those who live in the street. So Merton is crucial because he puts in writing the experience of many people who have, in some sense, practiced the contemplative life. He helps us to understand that you do not have to be inside a monastery to be a monk. He also teaches us that to be in tune with the soul is to be in tune with the world.

When Merton met the monks of Buddhism in the East, they not only had something in common because of the contemplative tradition but they had an affinity. It was as if brothers met, as opposed to practitioners met. It is not that they had something in common because of the contemplative tradition, the contemplative practice opened up an affinity that not only belongs to people who practice contemplation but belongs to humanity. The implications of Merton have yet to be seen. We are still looking at Merton’s biography, his boldness and insight. I think that we are on the verge of seeing that each one of these traditions holds a key that opens us up to the heart of what it is to be a human being.

Jeff: Another piece of insight that you have introduced me to is the Buddhist appreciation of emptiness. Why do Eastern philosophies and religions consider emptiness a gift, while western traditions fear it and even attempt to avoid it?

Emptiness is not empty. Perhaps, the more West you go the more empty emptiness becomes. The more East you go the more fertile emptiness becomes. Let’s say we are flying over the central valley of California in November. The hills have already been harvested and gleaned, so rather than see the green, you see the black of the earth. You could say the earth is empty, devoid of any growth. But the field is rich.

Many of us in the West fear the empty space. It’s empty; there is nothing there. I think the East is insightful. It’s not that there is nothing there, it’s that there is nothing obstructing; there is nothing in the way. If we look at a vacuum, there is nothing there. But if we look with quantum thinking, if you pay attention, it is surprising what appears. If I walk into a great room, is the room empty or is it open? This ties in deeply with the idea of no self, which strategically means to get the self out of the way.

If the doorbell rings and I open the door; there stands my friend Beverly. In order for Beverly to enter into the house, I have to get out of the way and create space. If there is no emptiness, Beverly can’t sit down. If there is no emptiness, Beverly cannot come in. And if I don’t get out of the way, I become an obstacle to the one I say I care about.

We might be able to appreciate this more if we get out of the idea that emptiness is an idea. It’s actually a way of behaving. It is creating space. It’s not that there is nothing here, but there is nothing that is obstructing you.

Jeff: Let’s switch gears here and talk about the Gnostic Texts. We had a discussion once and I remember it as if it was yesterday. I came to you one day and said, “Should I read the Gnostic texts?” You looked at me with your eyes wide and said “Of course.” So what are the Gnostic texts and why are they important to read?

I think you should read anything you can get your hands on. The Gnostic Texts are those documents found in Egypt around 1945 – 1948, like the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, and the Gospel of Thomas. These documents have been called Gnostic. Whether it is fair to call them Gnostic depends on what your definition of Gnostic is. The last time I looked at the definition, it was quite unstable. The Greek word Gnostic means “knowledge” and is based on the assumption that there is a secret knowledge of the heart, the way of mysticism that takes us to the experience of God. Beside all of that there is an implied cosmology, anthropology and psychology.

I think the Gnostic texts need to be read and appreciated because they tell us of the diversity and the fluidity of our history. The way we think today is not the way we thought 500 years ago, 1000 years ago, 1500 years ago or 2000 years ago. In the New Testament itself, you can see the diversity if you look at the Gospel of Mark, the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Book of Revelation, not to mention the book of Jude or First Corinthians for that matter. That diversity didn’t just suddenly end with the Book of Revelation or the Epistle to the Colossians. That kind of diversity persists to the present day. But it has been pushed outside the parameters of Orthodoxy. I think it is part of the human search. If we are going to understand the diversity that is in the world today, especially in Christianity, it does not come out of thin air. It’s not just simply rehashing what ancient people said, it’s using their methodology. They took the science as they understood it and philosophy as they understood it and used it as a way, a vehicle for soul searching, both as individuals and communities. So the more we are knowledgeable of where we came from, the easier it is for us to be who we are.

We would be outraged if someone had a thought we didn’t think. Truth doesn’t care who thinks it.

Jeff: You mentioned science and philosophy and how that intermingles with religion or how it used to do that. My wife and I always have discussions about the possibility of science and religion working together again. Do you believe that science and religion work to achieve the same goal and what would happen if scientists and theologians did work together?

The problem with that kind of a question is you need to define what you mean by science and what you mean by religion. Depending on the definition you give to science and religion, they can either work together or not work together. They could be cooperative; they could be perceptive of two different worlds at the same time.

I think the duality between science and religion is falling apart. I think those wonderful divides we used to have: this is the secular world, this is the sacred world, this is the invisible world; the invisible world belongs to religion and the material world belongs to science, are gone especially with the rise of Quantum mechanics. Now when you hear the creed, things visible and things invisible, the invisible doesn’t mean angels and demons. The invisible for us means all that stuff that is at the sub atomic level and particle level in the so-called vacuum, in the emptiness of space. The old separation of physical and spiritual is gone.

So I am not sure it is insightful to keep using words like science and religion when the words science and religion grew up in a different perception of reality than we now have. If you have a scientific world view that the world is mechanical, it’s like a well oiled machine and the purpose of science is to identify the parts, that’s gone. That whole idea that the universe is simply a machine has died or is dying.

There’s an interesting fusion between the biological sciences and the physical sciences. This universe might very well be aligned. So I am not sure that theologians and scientists can sit down and simply agree to cooperate. I think that scientists and theologians need to be humble about what’s before them and what’s around them. This is an attitude shift that will create a methodological shift.

In a certain sense we are in an in between period right now. Certainly science and religion cross over one another in the ethical field. But even then it’s no longer acceptable in the interfaith world to think that the concern of ethics is simply religious in the traditional sense of that term. For the atheists and the agnostics may have a higher ethical standard than the religious among us.

I think humility is the word right now and my experience in the scientific world is we know we don’t know. In my personal experience I hear more religious language among scientists than I do among religious. For example, “the awesome nature of the universe.”

Jeff: I brought my daughter into the center and it was a joy to just watch her explore and interact with certain things and touch certain things. She just took it all in. It reminded me of how important it is to have a child’s perspective especially when it comes to religion. Why do you think that is important?

One of my greatest experiences with interfaith work was in Pittsburgh, PA when we did the dedication of the center. The center would hold 800 people. The dedication day was done by children. The place was being dedicated for all the children who would touch it. Signs said, “Children please touch”. As children reached out and touched the artifact or the book, the book was blessed.

It’s my experience that children learn to separate that which they see as united and interconnected. Children instinctively search and seek. They become afraid and delighted. Their emotions are easily seen. Their questions are profound.

Jesus said the kingdom of God is like a little child. The kingdom of God belongs to little children. The words “kingdom of God” in the Greek does not imply a territory into which you enter but an energy that you are. You could easily translate it that the outpouring of God belongs to the children.

I think the child among us invites us to the child within us; to be fascinated and open; to be in touch with our feelings; to be where fear becomes reverence; where night becomes daytime; where the stranger becomes friend; where the scary becomes attractive; where the keep out sign is read as please open.

Jeff: Fundamentalism. Why is it important for people to learn about and to understand fundamentalism? When does fundamentalism become harmful?

I think you can identify in Christianity and in all systems there are 3 “isms” that are potentially deadly: fundamentalism, authoritarianism and traditionalism.

In any pathology, one has to be careful that one does not label people that are caught up in these energies pathological.

Fundamentalism can help us to understand the basis of what it is we truly believe. If ideology driven, it can be reduced to literalism that has no sense of paradox or human. I can damn you or I believe I had to kill you.

Authoritarianism: Jesus said the greatest among you is the one who serves the least. Authoritarianism can lead to domination rather than service. I have the right to dominate you rather than I have the privilege to listen to you.

Traditionalism: There is a difference between tradition that I hand on and traditionalism that believes that if it isn’t yesterday it cannot be tomorrow. So the church, the religion, the temple becomes a museum. I have the right to damn because you are not conforming to what I believe.

So the historical sense is lost in traditionalism, the service sense is lost in authoritarianism, and dynamism of the human spirit is lost in fundamentalism when they head toward their pathologies.

God didn’t give us the right to label, or condemn. It doesn’t mean we don’t have the right to diagnose. We don’t simply find these in other people we find these tendencies in ourselves. Interfaith work always demands that you are in dialog with yourself at least to the extent you desire to be in dialogue with the other, because it’s easy to slide into the fundamentalisms, the literalisms, the authoritarianisms and the traditionalisms where what I believe about God is more important than God.

Imagine for a moment if you were locked into what people believed about you and they felt no need to meet you because they thought they knew all about you. Notice what happens to yourself when you get locked into what you believe about yourself and never meet yourself. What you believe about yourself can be an obstacle to who you are. In spiritual direction one day, my guru said to me “I want you to meet someone” and I said, “who” and he said “you”.

Jeff: If interfaith work on a large scale continues to grow, how do you perceive the religious community 100 years from now? In terms of growing interfaith work, how will interfaith work affect religion and philosophy 100 years from now?

I will use an image. The faith communities of the world will look more like a wonderful ice cream store where there will be ice cream for everyone and no 2 flavors the same.

You cannot walk into an ice cream store and say I will have a scoop of ice cream. It’s impossible. There is no such thing as ice cream. It would have to be vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, tuti fruiti..You can’t get a scoop of ice cream. I think it is a profound image. No one is going to say chocolate is the same as strawberry. There is a grand discernment. Do I want this or do I want that?

One hundred years from now the religions will say what they are saying now. But the people who practice religion or spirituality or the philosophies will understand what we have in common is our humanity and not what we believe about humanity. What we believe about humanity and the divine and the sacred in the world is diverse much like the ice cream store. We might be better off if we savored each others’ insights and thoughts. I would think that in the individual tradition there would be a sense of openness to all traditions.

I would look for an increased diversity among the traditions and particular individual services or sharings that remind us that we belong to the human family in a cosmic dimension. I think we will look more and more like 7 kids in an ice cream store on a hot afternoon all coming out enjoying each others ice cream while firmly holding onto their own but not as a possession that is privatized and individualized but poised for the sake of the other.

Susan: There are many artifacts in the library. How do you personally relate to them? How have they affected your spirituality?

It goes back to is there such a thing as interfaith spirituality and if there is what would it look like, and how is it practiced? I had no idea what an interfaith environment was. I don’t think anybody does. What would it look like, what would you put into it? I had to start somewhere. I put in the center what I was able to collect with no rhyme or reason, except I like this, this looks good.

My experience is that if I am not in this kind of an environment, I don’t feel religious; I don’t feel spiritual; I feel like I am lacking something. I don’t belong to one tradition, while I can admire them; there is a side that says that I would like to bring them all with me. When I go to a Buddhist place, a Hindu place, a Catholic place, a protestant place, they become extensions of the interfaith sanctuary. In many ways the interfaith Center has become the Interfaith Sanctuary, the study place, the home place, the business place. I am not suggesting that is the way it should be or that is what people should do. Everyone has to work it out for themselves. That is part of the adventure.

One hundred years ago the word interfaith wasn’t used. Now every mainline tradition uses it. There is amazing shifts that we are caught up in.

Susan: How did you (Jeff) hear about IPP?

Last fall I was reading an article about the Interfaith Center. It mentioned an interfaith library. The last project I needed to do for my classes at Diablo Valley College was cooperative education, work experience, internship. I was shopping around and when I saw the article about the interfaith library, I emailed June and she immediately called me back and set up a meeting. She said the Interfaith Peace Project could definitely use some help cataloging all of the books. Working at an interfaith library would be a unique experience, so I jumped on it: cataloging all of the books, photographing the artifacts and doing research on how to preserve the sacred old texts. I began working in mid-January and graduated in May 2011. Three thousand five hundred books are cataloged with 500-1000 more still in transition.

Susan to Jeffrey: What were your thoughts when you first saw the library, the artifacts, the way the library was set up? I wasn’t expecting a residential house. I walked in and the first thing that I remember was feeling different once I stepped through the doorway. I detected something different, a relaxed comforting environment a sense of heightened awareness. The thought quickly vanished when I looked at all the books. I just detected a wonderful atmosphere that I rarely get to experience in life. I love libraries, but when I was here it was like a breath of fresh air an inner voice telling me this is where I am supposed to be and saying that “you are going to be changed just by being here.” June told me that I would not go away being the same person.

Susan: Jeff, how do you think you have changed? In a couple of simple, yet profound ways. I appreciate differences more; that differences are not a bad thing. Not just in religion, but in relationships, in ways of thought.

My wife and I are polar opposites. I have always appreciated how different we are. Because we are so different we have clashed sometimes. I have always appreciated her way of thought; her way of processing. My being at the Interfaith Center has helped me to appreciate even more how she thinks and processes and how much it compliments my way of thinking. It reminds me of the Yin and Yang way of thinking. She is the Yang to my Yin.

The library has helped me appreciate differences all over the place and not just in religion. It inspired growth, peace, understanding. There are the various differences I have learned about by just the process of reading titles and descriptions on the back covers.

I have come to realize that in the world religions there is one voice that can permeate through all of the religions. There is not just one way, there are multiple beautiful ways to tune in to and discover God’s voice.

I am learning a little about Taoism and self and I am finding that helps clarify my mind more to the point where I can ingest scripture in a better frame of mind. Before when I read the Scripture I just wanted to get through it. I didn’t ingest it; it didn’t change me whatsoever. I had so much clutter in my mind I was distracted. I was my own worst enemy. But now I am using Taoist principles to calm my mind, to find peace, to focus and when I read the Word it makes more sense to me.

Conclusion

The Interfaith Peace Project Library is a library for onsite use. The library was developed to provide a place for you to explore other faith traditions, to study, to meditate and to seek God in whatever sense God is understood by you, the seeker.

The library is available 6 days a week by appointment and on Wednesday from 11:00 AM to 2:00 PM with no appointment necessary. You are encouraged to come for a visit. If you would like to make an appointment or if you have any questions, please call 925-325-0144.